It’s a form of spatial theatre, but also spiritual theatre, since one is emulating saints and gods in the hope of coming closer to oneself, not just impersonating them for others. To walk the same way is to reiterate something deep, to move through the same space the same way is a means of becoming the same person, thinking the same thoughts. ‘A path is a prior interpretation of the best way to traverse a landscape, and to follow a route is to accept an interpretation, or to stalk your predecessors on it as scholars and trackers and pilgrims do. I share some of her reflections on ‘the path’ and on ‘the mnemonic’:

She for example states that sculpture gardens made the world into a book by situating events in real space, far enough to be ‘read’ by walking, even making Versailles or Stowe into books of political propaganda. In all her observations, space is a protagonist as important as the walker. She not only crosses interdisciplinary boundaries fluently, she makes me forget they are any. Rebecca Solnit writes like a poet, but her observations are sharp. As an architect, this triggers my imagination and feeds my ideas into my own field of designing.

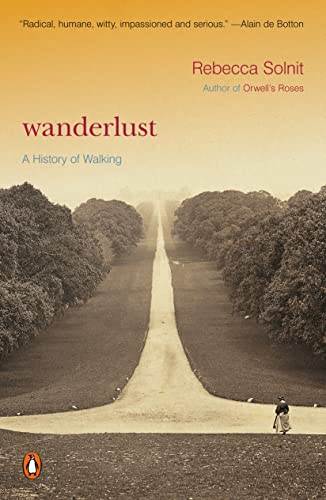

Reading this book is like wandering through a garden of thoughts. Walking within a landscape or the city is often an analogue process to philosophical thinking processes. From the perspective of this physical dimension, Solnit lets people bodily enter a story. Whatever the story or background, walking is always put in relation to the space that is walked in or at. In her book Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit unravels walking throughout time as a bodily experience interwoven with culture, politics, and society.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)